Russian Banking's Birth by Mutiny

Part IV of a Discussion on the Operational Details of Russia's Transition to Capitalism

Part of a series on the operational details of Russia’s transition to capitalism

We hardly need to take the United States as a model.

It is a country with its own painfully specific features. We must not forget that it is 200 years old and has been settled mainly by rebels, adventurists, and misfits, by what one may call dissidents who did not get on in their native civilizations and were drawn to the undeveloped continent, where they could do, think up, and try whatever they liked.

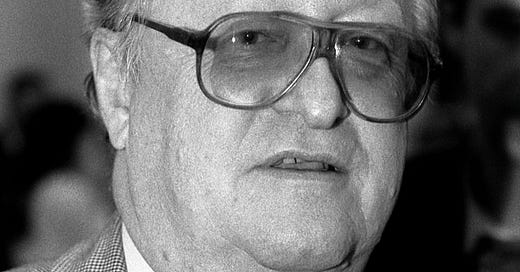

— Viktor Gerashchenko, head of Gosbank, in 1993

In Part III, we sketched out Soviet banking’s final stable form. Today, we’ll walk through the play by play of how it collapsed, and how through its collapse, modern Russian banking was born.

In Part III, I argued1 that the Soviet banking system was designed with a cardinal goal of eliminating the ability to transfer price information. Why was it such a critical, uncompromising policy goal to avoid price signals? Because prices created opportunities for arbitrage and profiteering, which the Soviets saw as criminal. Article 153 of the Soviet legal code explicitly outlawed “private entrepreneurial activity”, punishable by a “deprivation of freedom” of up to 3 years.

All financial activity in the entire Soviet Union was handled by a single bank, called Gosbank (“government bank”). It managed a two-tier monetary system, where two types of rubles circulated, on two totally separated circuits of trade. Worker wages and purchases were paid in the domestic “hard” ruble. State owned enterprises—the only multicellular organisms permitted in the Soviet economy—traded with each other in “virtual”, cashless rubles.

The best available English language literature seems to indicate that Gosbank’s only monetary instrument was the ability to issue new virtual rubles. It did so by directly crediting the virtual ruble accounts of individual enterprises.

But how do you know which businesses most need credit subsidy? Any bureaucrat worth their salt will tell you that you can’t terraform turf you have not properly mapped. In order to map out the Soviet economy’s balance sheets, Gosbank maintained the authoritative account of all inter-enterprise debts.

Never mind that this system—a purely virtual currency, whose entire transaction history is stood in a single authoritative ledger—is identical to a blockchain, except that the Soviet solution to the Byzantine Generals problem is to have only a single General.

Anyway.

Previously, I compared the birth of the Russian banking system to a zombie outbreak. The Soviet Union’s previously dead banking institutions sprang to life with a new sense of agency as the banking monolith fell apart. As more players within the system realized for the first time they had agency, it accelerated the collapse of the old Soviet banking model, and birthed the one we have today.

Act I: The Monobank Fission

Every zombie story starts with a case zero scene. In this story the outbreak started with the Law on Cooperatives of 1988, which legalized private enterprise in the USSR. It did so in part by making state owned enterprises responsible for their financial performance, meaning they would have to go bankrupt if they failed.

Now this wasn’t something one could simply declare. It required changes to the structure of banking. In order for it to be possible for businesses to go bankrupt, their access to credit need to be mediated by market forces. But all commercial credit in the Soviet Union was doled out by Gosbank to state enterprises, in the form of virtual rubles. The newly realized market agency of state owned enterprises needed to make a zoonotic hop to Soviet state banking.

There was probably a wood paneled room somewhere in Moscow with an oblong table, where Soviet economists gathered to deliberate how they might create a credit market. “Well of course,” one of them probably said, “we need to carve up Gosbank into a proper two-tier banking system.” That’s essentially what they did, splitting the monobank into an upper central bank, and lower banks that allocated credit.

The lower tranches of Gosbank were spun off into 3 special purpose banks called spetsbanks (“spec. (as in special) bank”). These spetsbanks would be more actively involved in the provision of credit, taking from Gosbank its responsibility of dealing directly with commercial customers. The spetsbanks would make lending decisions based on their assessments of the creditworthiness of businesses requesting credit. This meant Gosbank would lose its only monetary instrument of directing credit to individual businesses. In its place, Gosbank gained the ability to set interest rates at which the spetsbanks could borrow from it.

Gosbank Strikes Back

Gosbank was very unhappy to see these market reforms break its monopoly over Soviet finance. And because the carve-up left fuzzy mandates and overlapping scopes, Gosbank and the spetsbanks immediately began feuding.

In a Total Soviet Move™, Gosbank attempted a denial-of-service attack on the spetsbanks by barraging them with telegrams, memos, directives, forms and other paperwork that were meant to overwhelm the spetsbanks’ organizational processing power. The spetsbanks, in a Total Soviet Response™, hired more staff to clear their backlogs of Gosbank correspondences.

Gosbank tried to restrict the credit available to spetsbanks. The spetsbanks, knowing their privileged monopoly of credit shielded them from any real market accountability, gave out credit to enterprises like it was candy. Seeing the overstaffed and over-levered spetsbanks, the Soviet Council of Ministers thought the core problem was a lack of profit motive. So they passed a resolution that required the spetsbanks to operate out of their own revenues.

But mostly all this did was heighten the stakes of the feud between Gosbank and the spetsbanks, who now had fewer places to turn for bailouts (or financial armaments?) as they thrashed under Gosbank. The real problem wasn’t a lack of profit motive, but an unusual failure in the lending supply chain: Gosbank wouldn’t avail enough credit to the spetsbanks.

Normally, when central banks tighten their monetary policy, they do so for the sake of the currency they manage, to help stem its inflation. But in this case, Gosbank tightened its credit availability to strengthen its control over the spetsbanks.

Practically every state enterprise was exposed to the waste heat produced by this infighting. The state banks had no uniform operations, and they each offered different subsets of the banking services suite. In summary, every enterprise had to deal with all the state banks. For example State Bank A offered settlement services, while Bank B offered working capital, Bank C offered payroll loans for your workers, and so on.

Cooperatives as a Financial Wormhole

As the state banks bickered, the heads of the state enterprises realized that the Law on Cooperatives had opened a novel pathway for them to convert their outputs, which were normally only sellable for virtual rubles, into cold hard cash.

Previously the state enterprises were only able to trade with each other, and could only settle their transactions in virtual rubles which were valueless and inaccessible to Soviet citizens. If you were an individual, there was no way to use a virtual ruble to pay for your rent, or for a dozen eggs, or a bottle of vodka. In fact, there was no way for you to even hold a virtual ruble—literally because 1) there were no material, physical banknotes (hence their “virtual” moniker), and 2) in a property-rights sense there was no way to open an individual account at a Soviet financial institution that could accept virtual rubles. This was the Soviet two currency system, and it was meant to shield Soviet production from price signals and subsequent profiteering.

Well the Law on Cooperatives allowed these state enterprises to open subsidiary cooperative entities. These cooperatives were allowed to interface with the open market and deal in hard rubles. For the first time, Soviet enterprises could sell the goods they had created for real, paper cash. Cooperatives were a financial wormhole that allowed enterprises to alchemize value that was previously trapped in virtual ruble funny money into hard cash, which could be used by end consumers and were therefore infinitely more valuable socially.

This was the moment it became clear that the Soviet economy had not been built in the absence of markets, but in a market vacuum. This was the moment that that vacuum burst. And as enterprises began pushing their product through their cooperative wormholes, they began to build massive piles of hard rubles with nowhere to put them to work. And just as much as nature abhors a vacuum, money abhors unemployment.2

Letting a Thousand Cooperative Banks Bloom

There was a massive and growing unmet demand for banking among the cooperatives. In 1988 Gosbank, under the leadership of its new director Victor Geraschenko, realized this presented an opportunity to dilute the spetsbanks’ control over the Soviet credit system. Gosbank, as the Soviet Central bank, was responsible for authorizing banking charters. It deliberately slashed the requirements for cooperative banks, allowing them to form with as little as 500,000 rubles in charter capital.

These new banks could exploit multiple arbitrage opportunities between the imploding command economy and the exploding market economy. They accepted hard cash deposits from the wormhole cooperatives and lent them out to those credit-starved firms building outside of the command economy. So now, not only was value leaving the virtual ruble system through the cooperative wormhole, but it was beginning to compound as it sat in accounts at freshly chartered private banks.

Because veto power to register a bank was still promiscuously distributed across many organs of the Soviet apparatus, most of the market demand for banking was served by cooperative banks that kicked up a cut of their action to either a state enterprise or Soviet administrator. Many of these banks formed to serve only one to three clients, usually large state enterprises who had grown disgruntled with the deteriorating state banking system and decided to convert their finance departments into single-client banks. Federov estimated that “pocket banks” accounted for at least 75% of the capitalization in the new commercial banking sector by 1989.

Gosbank’s push to accelerate the expansion of the banking universe put pressure on the spetsbanks, and there were more than 70 banks operating in the USSR by 1989. As more commercial banks formed and scaled off their own cashflows, they began draining the government banks of their best, most enterprising talent.

The spetsbanks didn’t take this threat lying down. They tried their darnedest to obstruct the new commercial banks. They’d refusing to open spetsbank accounts for them, which the new banks needed them access to the interbank settlement network. They’d freeze the assets the private banks held at their spetsbank accounts, or refuse to transfer funds to the their customers’ accounts.

Act II: A Bank Mutiny

From 1988 to 1990 more and more of the banking system turned hostile towards the spetsbanks.

In 1990, a political wedge formed as Boris Yeltsin, newly elected as the chairman of the Russian Soviet republic, distanced himself from Gorbachev’s unity-focused reforms. In July of that year, the USSR Council of Ministers moved to keep the spetsbanks under Soviet rather than Russian control. They announced that they would flip two of the three spetsbanks into commercial joint-stock banks, and give a controlling share to the Soviet Ministry of Finance.

This culminated in a banking secession. Within days, the Supreme Soviet of the Russian Federation (the Russian republic within the Soviet Union) called for the creation of a two-tiered banking system within Russia, and that all spetsbanks within Russian territory would be under the jurisdiction of the yet-to-be-formed Central Bank of Russia (CBR).

Gosbank, in yet another Total Soviet Move™, responded by sending out a telegram to the entire Soviet banking system to ignore any local legislation that contradicted their laws. And then it informed all the state banks that their computer networks would be comandeered by the Gosbank head office.

Ah yes. Telegrams and control. You get em, Gosbank! Flex that rational-legal bureaucratic authority. Here’s the problem, though. When order gets disrupted, rational-legal authority gets you a lot less mileage. This is because the rules are melting. The clay that had previously been kilned is un-drying. Proactivity now has much higher leverage than your rule kugel. Don’t things that don’t scale can move mountains because laws and offices and bureaus have decomposed, and we’re back to what’s it been all along: just people dealing with other people.

The Russian Federation, in its monetary battle with the Soviet Union, seems to have understood this in a way that Gosbank didn’t. At this point, the CBR was merely a figment enshrined in a series of documents. It controlled no accounts, it stewarded no currency. Insofar as it was anything at all, it was just a piece of paper.

Every eventually powerful institution starts out like this, just an idea. What brings the idea to life is action.

And in this crucial moment, the CBR’s founding chairman, Georgy Matyukhin, previously an economics researcher, behaved like you might expect a promising startup founder to immediately after they complete their incorporation paperwork. He moved—physically, with his body—to make his idea real. Here he explains it in his own words:

Then it was necessary to create the bank and find myself a place under the sun. The Russian …[branch of] Gosbank was located in Moscow. I directed myself there. But, despite the resolution [issued by Yeltsin]… they simply didn’t allow me into the building… Then I decided to “storm” the bank with a group of Russian deputies… Fortunately our “storm” succeeded, and [one of the deputies with ties to the Moscow Gosbank branch] introduced me to the staff of the bank, saying that in agreement with the resolution a Central Bank must be founded, and it would be desirable not to start from scratch but on the basis of the already existing bank. The collective supported this idea and we began to work.3

So Matyukhin successfully flipped Gosbank’s most important provincial branch into a totally new central bank, with the consent of the bankers.

Reader, can we just stop for a moment and take in how absolutely weird and unprecedented this is? When we think of seismic changes like this, they usually happen downstream of tanks rolling into presidential compounds, or civil wars. But here, both bloodlessly and without threat of force, an economist went up to the strongest regional branch of his government’s central bank, and told them “you guys wanna peel off and do our own thing, just for this region?”

To transpose it to more local landmarks, this would be like a professor of economics at Columbia, acting on an executive order issued by the governor of New York, marching to the New York branch of the Fed and successfully talking the staff into monetary defection to the newly sovereign Republic of New York. And that all Jerome Powell did in response was send out a press release saying “I vehemently disagree” and then threaten to have the Fed’s head of IT reset everyone’s passwords.

This Is, very, very weird.

But—

It’s what happened.

Matyukhin then offered all the individual spetsbank branches within Russian territory the opportunity to “go private” and become for-profit entities if they registered under and transferred their assets to CBR. By the time Gerashchenko made a similar counteroffer it was too late.

Thus began a wave of thousands of spetsbank branch administrators weighing their options. They deliberated whether they “go private alone” or merge into clusters with other neighboring branches to take advantage of larger consolidated balance sheets.

This privatization of the spetsbank branches was a watershed moment in how Russian capital would form. The initial capital required to register with the CBR was often provided by the handful of state enterprises each of these branches served. So when the spetsbank branches were incorporated as private commercial banks, the shares in those banks went to the state enterprises (who themselves were on a completely uncharted path to become private joint stock corporations).

Knowing that the institutional clay would not be this malleable for long, CBR moved fast to approve spetsbank privatizations and registrations. One branch manager says:

Strangely, we registered without any problem. The resolution “On Commercial Banks” was passed in the beginning of October 1990, and on October 31 we had already received in Moscow all of the necessary documents and status of a commercial bank.4

This was the second banking explosion, after Gosbank encouraged the formation of cooperative banks.

The result was that by late 1991 Russia had nearly 2,000 individual banks, where just 4 years prior there had been 1. As Juliet Johnson points out, this didn’t lead to a vibrant, robust banking system, with banks cooperating with each other to increase the availability of worthy credit to worthy borrowers. Instead it led to turf wars between newly formed banks jockeying for each others deposit fiefdoms, and the birth of thousands of undercapitalized banks, dangerously close to failure as soon as they were incorporated.

It also led to a brain drain from the central bank. Commercial banks poached CBR’s most talented new recruits. Within a couple years, fewer than 1 in 5 employees in Russia’s central bank had a college degree. And the majority of them were legacy hires from the Gosbank days, culturally bound to the Soviet way of pushing paper.

The bank privatization happened so fast and so politically that it didn’t get to incorporate foreign investors into the process the way other Eastern European countries like Poland did. In those countries, foreign investor involvement made the whole process less volatile, as outside expertise helped restructure banks and transferred desperately needed institutional knowledge about how to operate in a market economy.

Russia’s New Banking System

So now, after much thrashing and struggle, Russia had fashioned itself a new banking system. The Central Bank of Russia was a totally new creature in the history of Russian finance: a fully autonomous steward of a modern fiat currency, floating on international markets. Following the tradition of central banks in the West, the CBR was autonomous from the rest of the Russian government.

Normally, the theory goes: keeping central banks autonomous lets them implement sound monetary policy even when it’s unpopular (people love loose money but that eventually causes inflation, and people hate being credit starved, so tightening the money supply—usually the only way to really combat inflation—is an inevitable necessity, even if politically unviable).

So autonomous central banks can protect a currency while staying insulated from political blowback. This is a very bazaar-pilled cybernetic approach: autonomous central banks can respond to the economy without the pressure of election cycles.

What’s unique about CBR’s autonomy is that it was an absolute menace to both the Russian government above it and the commercial banks beneath it. It operated opaquely, providing almost no visibility to the public, the legislature, or the executive. And much to the frustration of the commercial banking industry that it spawned as part of its banking mutiny, the CBR was sporadic in its rates. They’d suddenly skyrocket, and then plummet without warning. This was in part because there was no real consensus within the CBR about how it should apply its monetary instruments.

This made lending hell for commercial banks. Don’t cry for them though: they still made a handsome profit despite this chaos by lending at exorbitant rates to credit famished entrepreneurs. Many of these entrepreneurs themselves were making a killing despite the high costs of capital by running the wormholes that converted virtual-ruble-denominated state production into hard rubles.

Act IV: Banking Infrastructure Strikes Back

The most interesting thing about Russia’s banking transition, besides everything, is the way that it put infrastructure center stage. This is a general property of crisis: stress tends to make implementation details critical.

Recall how we described the pieces of Gosbank’s infrastructure as a series of Chekov guns. For CBR, it was immediately confronted by two problems.

Great Expectations. In 1992 alone, the nominal value of loans made by commercial banks grew 10x. Despite hyperinflation, banks turned sizable profits off lending due to a massive interest rate spread between their deposits and loans. They also had another cheap source of capital: the CBR’s directed credit policy.

The CBR continued Gosbank’s directed credit policy, but it relied on commercial banks to handle the implementation of allocating the credit to specific enterprises. This effectively made the commercial banks the enterprise-level servicers of industry-level credit issued by CBR. As part of this arrangement, the credit that commercial banks received from CBR could only be allocated businesses in the intended industry, and at capped interest rates.

Commercial banks happily ignored these restrictions because they knew the CBR didn’t have the capacity to granularly monitor what happened to the credit after it had been transferred to them. The result was both surges of credit in industries that the CBR did not intend to target, and windfall banking profits despite hyperinflation.

By May 1992, it became clear to CBR that the Gosbank-era card file system had helped create moral hazard that enabled the ballooning debt balances. The problem lay with card file number 2 channel in particular, which gave CBR (and Gosbank before it) fully visibility into all inter-enterprise transactions.

Previously Gosbank’s policy of directed credit would allocate virtual rubles to insolvent enterprises. CBR saw that as long as card file number 2 remained open, the market would saddle it with the same expectations. So while it offset debts for the final time in the summer of 1992, it abruptly announced the closure of card file number two.

This signaled to businesses that they had to figure out their own finances.

Payments bottlenecks. The most significant infrastructural failure was also the most straightforward. The CBR found itself running a much more interconnected banking sector using centralized infrastructure. Every. Single. Bank payment in Russia went through the CBR’s settlement system. This meant every transfer had to be processed by hand, with pen and paper, at CBR’s head office. To make matters worse, as the CBR was still on the dual-circuit Soviet ruble, it needed to process these payments across two separate channels.

If this was arduous for the central bank, it was torturous for the commercial banks. Interbank transfers took about two weeks to complete on the paper system, as it was swamped by the hundreds of hundreds of transfers happening between Russian banks.

The CBR tried to streamline its payments workflows by repurposing yet another piece of Gosbank infrastructure, this time the payments-cash centers which Russia developed to remit its taxes back to the Soviet budget, called RTKs.

The rollout was one of the most consequential migration failures in the history of systems. Overnight, it created even bigger piles of new paperwork for CBR staff to process. It wasn’t clear who to send what documents to, so many commercial banks had to hire full time staff whose only job was to navigate how to get their transfer slips processed at the local payments-cash centers.

Many banks had employees who stood in line for weeks at a time just to get their bank’s cash out of these centers. Interbank settlements in Russia were already shambly, but the migration to using RTKs pushed the problem over the edge. The migration was such a mess that it contributed to Matyukhin losing his job when the Russian parliament’s called a vote of no confidence against him in 1991.

His successor?

No other than former Gosbank head Viktor Geraschenko, the same person who had attempted to thwart the formation of the CBR in the first place.

Conclusion

It’s quite hard to cinch shut a history on the birth of the modern Russian banking system, because it’s a process that is still ongoing today. In many real ways too, not in the cosmic “everything is always in motion” senses. But this was Russian banking’s big bang moment. The immense pressure from the blast was so strong that it triggered revolts at the highest levels of government. It left melted payment systems in its wake. It sucked in the deftest minds of the previous order and kneaded their talents into its sourdough, shooting ever outward.

Monetary mismanagement and economic shrinkage led to the implosion of the Russian ruble in 1997, a financial meltdown that wiped the country’s savings.

While true of any banking system, Russia’s final chapters in particular are far, far from written.

Even though we can’t get all the way to present-day, in the next (and, I promise, final) installment of this series, we’ll discuss the demise of the Soviet Ruble zone.

Bibliography

Fedorov, B. Reform of the soviet banking system. Communist Economies, 1(4). 1989. doi:10.1080/14631378908427623

Johnson, Juliet. A fistful of rubles: The rise and fall of the Russian banking system. Cornell University Press. 2000.

Johnson, Juliet Ellen. The Russian banking system: institutional responses to the market transition. Europe-Asia Studies 46.6. 1994.

Kim, Byung-Yeon. “Causes of Repressed Inflation in the Soviet Consumer Market, 1965-1989: Retail Price Subsidies, the Siphoning Effect, and the Budget Deficit.” The Economic History Review, vol. 55, no. 1, 2002, pp. 105–27. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/3091817.

Nakamura, Yasushi, and Yasushi Nakamura. "Soviet Banking and Non-cash Money Management." Monetary Policy in the Soviet Union: Empirical Analyses of Monetary Aspects of Soviet Economic Development (2017): 99-124.

The exact motivations of why the bank was designed as it was are encoded in arcane debates about political and economic theory. The debates are all in Russian. And they are far along in their sink into the sands of time.

For those following along, you might wonder, why exactly, the arrival of the cooperative wormhole didn’t collapse the virtual ruble system. From the best that I can deduce, it seems that a lot of virtual ruble allocation happened as annual budgets for state enterprises, besides the policy of direct credit that the spetsbanks took over as commercial banking. Also, I think while the wormhole flow was significant, the market was still quite nascent so the rate of flow probably had limits. We’re left speculating until someone can dig up the detailed mechanics of exactly how virtual ruble allocation worked.

Fistful of Rubles p. 47.

Fistful of Rubles p. 52.