Why Russian Companies Sought Mafia Protection in the 90s

Part II of a Discussion on the Operational Details of Russia's Transition to Capitalism

In the previous post of this series, we discussed how, and why, the Russian market was born in crisis: it was everyone’s first time doing things that can take a career to master. Because every business was figuring out how to manage its cash cycles, every lender its loan book, and every central banker the economy’s very currency, there were so many ways for a transaction to go wrong.

Russian companies were desperate for help in enforcing their contracts and collecting unpaid debts. The Russia government in the 90s, never having supported private enterprise before, wasn’t very good at this. This forced many businesses—far more than you might expect—to seek rule of law from enforcers made by the chaotic formerly-criminal market, for the chaotic formerly-criminal market: mobsters.

Time for a story about promises and how they are enforced.

Business is Just a Chain of Promises

Every business, supply chain, industry, and economy is held together as a series of promises. That’s because just about every transaction has a promise baked into it.

In the most basic form, if your business needed a loan you might say, “I promise I will pay back the value of this loan, along with the agreed upon interest, by the following date”. The promise of repayment is probably the most common promise made in all of business.

Most often the promise of repayment isn’t made in exchange for money, but for inventory. When you go to your neighborhood hardware shop, the hammers and screwdrivers and saws on their shelves are all purchased on credit terms. If you live in a developed country this is probably true for just about all merchadise see on all shelves of all stores. Suppliers offer their customers credit because inventory takes time to sell, and it’s only when the sale is made that the store has enough cash on hand to settle the original invoice for the inventory.

These promises don’t just govern debt transactions, but also transactions involving equity of the company itself. When someone invests in your company in exchange for ownership they’re accepting a promise as well. The promise your company is making isn’t about future repayment per se, but rather that the claim on the ownership of the company is real. This is a concern that only matters at some future point when your business has taken the investment money and made productive use of it.

Capitalism—i.e. a system in which people organize their productive efforts to accumulate money—is only possible because of promises. At the heart of every capital accumulative loop is a promise. That’s because accumulation happens over time, and promises are commitments that we make to each other about the future.

In the early days of the Russian market, it was very hard for businesses to keep promises because no one had ever done business before. To reduce your exposure to bad promises, you could tighten your circle of trust and limit who you traded with. Most businesses did. But even if their trading partners were trustworthy and meant well, the chaos meant there were all kinds of ways they could slide into insolvency. So when things got messy, how could you ensure your counterparties kept their promises?

The Guarantor of Last Resort for a Promise is the Rule of Law

All promises need recourse in the case that they’re broken. To some extent that recourse can be reputational. You could, for example, trash talk promise breakers to everybody you meet in your industry. But telling people that you were lied to you or stiffed for an invoice won’t fill the hole in your balance sheet. The only way to remedy the situation is to force them honor their word, preferably through a third party who will do the forcing for you.

That’s where rule of law comes in. A good rule of law can efficiently and predictably adjudicate economic disputes and ensure people get what they’re owed, to the fullest extent possible. When it does its job well, it even acts as a deterrent for bad behavior. And when businesses have a rule of law that they can rely upon, they’ll be able to do the magical promise stacking that allows them to grow.

So if you’re a business owner, you’re in the market for rule of law. For you, “rule of law” was not some lofty ideal that politicians, from Brezhnev to the Bushes, reach for in their speeches. It’s a tactile service with vendors who you can evaluate as concretely as you would an accountant or a plumber.

Soviet leaders hastily created a market and then shoved their state enterprises into that market and then plunged that market into turmoil. So they not only created a new demand for rule of law. Through the chaos caused by their mismanagement, they also pressurized that demand.

Let’s look at what vendors you had to choose from if you were in the Russian market for rule of law, starting with the incumbent.

The Russian State Had Never Enforced Ownership Promises Before

It’s best to start with the state’s enforcement of company ownership rights, because states are really the only ones that can enforce this type of promise in a way that makes it a tradeable commodity, e.g. a share on a public stock exchange. Also, ownership rights are most relevant for more complex corporate entities with a large list of shareholders. At the dawn of the transition, all the companies that fit this description were former state enterprises.

A lot of company ownership protections simply hadn’t been built yet. It’s never a great time to speed run to capitalism. But Russia’s leaders had many, many other fish to fry when they did: a failed coup attempt, a political breakup that created 15 sovereign governments, figuring out how those governments would work. So as a result, in the frenzy of privatizing their economy, they had some… oversights around the very basics of protecting ownership.

You can see this in the story of an airplane parts factory that transitioned from state to private ownership in 1991. The managers wanted to give workers ownership in the factory. Getting the details right was important: they had 15,000 workers to add to their cap table. So they consulted “Soviet experts” when drafting their documents. Eventually management realized that they had screwed up and created an organization that failed to protect the interests of any stakeholder—be they employee, manager, or shareholder. They sought advice on how to fix their mess-up, in a process that went roughly like so:

Management: “Well can we seek the guidance of securities regulators, like the Russian version of the SEC?”

Advisors: “Mmmmm, securities regulators don’t really exist yet.”

Management: “Ah, ok —no worries! Perhaps we can reach out to a corporate lawyer then who can help get us back on track?”

Advisors: “Yeahhh, those don’t really exist yet either.”

Management: “Shareholder advocacy groups?”

Advisors: “Those don’t ex—”

And it wasn’t just supporting institutions (and professions!) that were missing.

Russia’s first corporate laws lacked basic details needed for enforcing property rights. The first statutes on corporate organization, passed in the late 80s, boiled down to “C’mon you rascals! Shake hands, do business! It’s legal now!” They had zero guidance on the most basic shareholder rights, such as:

After I get shares in a company, can I sell or transfer them to someone else?

Does owning equity allow me to participate in the company’s management?

What rights do I have to access information about the company’s financials?

What fiduciary duties does the company’s management owe me?

Where can I turn to enforce my shareholder rights?

In short, there were a lot of dotted-line silhouettes with I.O.U. sticky notes in them. While they had a lot to figure out when it came to shareholder rights, the Russian state quickly got to work on adjudicating economic disputes.

The Russian State Was Only a Little Better at Enforcing Debt Promises

Most businesses rely on credit-related promises far more than equity related ones. Credit promises are more important for scaling up a business’s cashflows—quality dispute resolution creates less credit risk, which lowers the cost of capital, which makes it cheaper to unlock tomorrow’s cash today. In short, better rule of law makes it cheaper for a business to press the fast forward button on its growth. So how, exactly, did Russian courts handle the issue of promises around credit?

Their solution was repurposing the Soviet court that adjudicated disputes between state enterprises. That court was called gosundarstvennyi arbitrazh, or gosarbitrazh (“state court”). With the rise of private businesses, Russia introduced a successor to gosarbitrazh called arbitrazh (“Drop the gos”, Justin Timberlake tells Jesse Eisenberg, “It’s cleaner”).

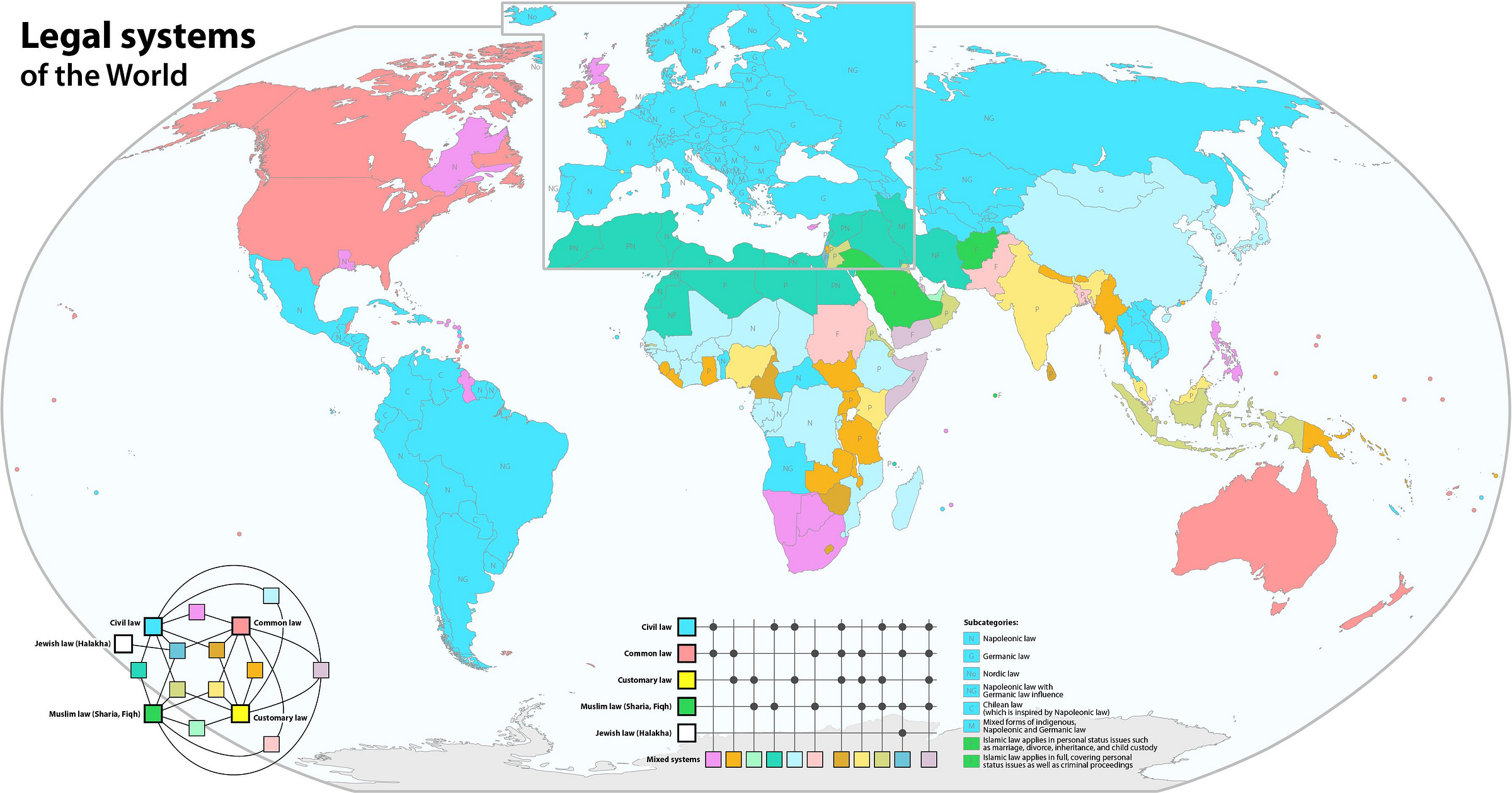

Arbitrazh courts operated under a legal tradition that was completely new to the Russian justice system. Russia’s court systems were all built in the civil law tradition, which inherits from the system of law used by the Roman empire for its citizens (hence “civil”). Civil law is the dominant model of law in Europe.

But Russia’s arbitrazh courts were modeled on common law, the system of law used in Britain and its former colonies, including the United States. (Sidebar: After reading hundreds of pages of The Literature, I still haven’t found a clear reason as to why arbitrazh is a common law court.)

A dollop of humility: legal genealogy is a discipline to which many outstanding historians and lawyers have dedicated their entire careers. There’s more nuance to it than we can fit in the HTML payload of this humble newsletter.

With that said here are the basics of how, exactly Russia’s civil law-trained legal professionals struggled with arbitrazh’s common law flavor.

First, Russian lawyers had never carried the burden of proof before. In civil law courts, the rationale for decisions comes primarily from the statutes on the books. The model of justice in civil law trials is inquisitional: they’re driven by the judge, who requests evidence from the petitioner (the person or entity who files the case) and the defendant.

In common law courts on the other hand, the rationale for decisions comes from precedents set in prior cases. The model of justice is adversarial: trials are driven by the petitioner and the defendant who prepare and present the most persuasive evidence they can to the judge. This means the parties carry a burden of proof in establishing their respective cases. The petitioner presents evidence to demonstrate the guilt of the defendant, while the defendant must contest the accusations made by the petitioner with their own evidence. If the petitioner fails to present convincing evidence to prove their case, they lose. If the defendant fails to present convincing evidence to rebuke the petitioner, they lose.

These were totally new norms, which created a frequently occurring comedy sketch that played out in arbitrazh courtrooms across Russia.

Judge: “Ok petitioner, please present your case”

Petitioner Lawyer: *stands up, tersely re-reads the contents of his or her petition to file the case with the court*

Judge: “Please present your evidence to the court.”

Petitioner Lawyer, blushing: “Evidence, your honor?”

Not all judges were consistent in their demands that lawyers prepare proper evidence. Judges who had entered the Russian court system after the formation of arbitrazh had an easier time. These new procedures came naturally because they had a blank slate of how judging was supposed to work.

Older judges who had served in the Soviet gosarbitrazh had old habits to unlearn. Stuck in their civil law ways, these elder judges were less likely to enforce the new burden of proof requirements. They also struggled with the new responsibilities demanded of them by common law.

Russian justices had never had to document the rationale for their decisions before. Civil law decisions do not need the same detailed rationale as common law decision. Decisions rarely exceeded 2 pages, which is “baby shoes, never worn” levels of short in the word-philic realm of law. But in common law, judges need to write detailed decisions. Documenting their decision rationale establishes precedent that will be used to resolve future cases with similar fact patterns.

But this is a totally new skillset for the median 90s Russian judge. And the midst of a crisis that blows up demand for your services is not a great time to learn new skills.

This all meant slow resolutions for arbitrazh cases. Arbitrazh had a statutory service level agreement that it would render decisions no more than 2 months from filing. But most cases from 1993-1997 took closer to 4 months. And thousands of arbitrazh cases were stalled for over a year. These slow timelines were agonizing to business owners: as arbitrazh took its time, hyperinflation was decaying the underlying value of the claims they were filing for.

Common law, shmomon law - the REAL problem was enforcement. At the dawn of arbitrazh in 1992, Russian justices had never forced independent companies to comply with court orders before. In the gosarbitrazh era, decisions executed as smoothly as a piece of software—they were a transfer of funds from one state wallet to another. Making independent businesses comply with these laws was a different beast altogether.

For most of the 90s, arbitrazh courts had no dedicated enforcement officers. Instead, they had to rely on the spare capacity of sadebni izpalniteli (“bailiffs”), who enforced decisions for the general civilian courts. When the bailiffs did enforce, they had a whole new learning curve to climb. Enforcing arbitrazh findings required a totally different skillset from the usual beat of general jurisdiction enforcement. Collections for a typical arbitrazh case might require officers to seize hard assets—think tractors, CNC machines, pallets of plywood, or chicken cages—from the defendant company, and then find buyers to purchase the assets in exchange for cash, which then would go towards settling the petitioner’s claim. That’s totally different skillset from a typical general jurisdiction case, which involves stuff like chasing down absentee dads for child support.

In well-functioning justice systems, defendants comply with court orders because of the legitimacy of the court and the consequences of non-compliance. The arbitrazh courts, still nascent, had neither going for them. So the entire enforcement process was driven by petitioners who had to push resistant, overworked court officers to do their jobs.

Even when petitioners did try to collect, the process was agonizing. The typical enforcement workflow was convoluted. First the court would tell the defendant to pay. When the defendant didn’t (because why would you listen to a new court that can’t enforce its decisions?), then the petitioner would ask the court for an enforcement order. The court would issue the enforcement order, forcing the defendant’s bank to pay the petitioner. The bank would reply to the court: “sorry lol insufficient funds, apparently they emptied their account last month?,” but in legalese. Petitioner would request help from the bailiffs, who are statutorily required to resolve the case in 20 days (narrator: they don’t).

And then one of two final scenes, either: court enforcers fail to find the defendant at their registered address, cold case! Or they DO find the defendant, but they don’t have the trucks or vans to take their assets back to the arbitrazh warehouse for liquidation. Because who among us remembers to account for transport capacity when we’re architecting our country’s first commercial court? Or more commonly, they’d find nothing there.

Defendants had many ways to play dead. To shield their funds from seizure, they’d open multiple accounts for their business. They’d siphon funds from their main checking. They’d transfer their assets to shell companies. They’d transfer their company’s assets to their own personal ownership. They’d register assets under the names of wives, siblings, trusted managers. They knew that Russian courts wouldn’t break the limited liability boundary to collect debt, a practice known in lawyer land as piercing the corporate veil.

Successful enforcement was uncommon—the most optimistic sources say 50%, but many sources estimate as low as 20%. Even if you did manage to collect, from filing the case to wiring the restitution, the arbitrazh process could easily take more than six months.

Did I mention this was 6 months during hyperinflation? If you think I’m overstating hyperinflation, then I’m probably stating it the right amount because it was on top of the mind of every business owner who was owed money. Hyperinflation put a very real and sizeable monetary value on enforcement speed.

The arbitrazh courts were backlogged with cases as lawyers and judges learned how to dance to the tune of common law. Decisions were enforced by ineffectual, overworked court officers who treated commercial cases as a second job. When they did enforce, defendants played shell games to hide the money they owed.

But the sky was still falling, even if the Russian courts couldn’t catch it. Businesses, desperate to escape this chaos, felt a burning need for order. They needed the promises that were made to them to be kept, even if by force. And they were ready to pay handsomely.

With all that pent-up demand, a functioning rule of law was bound to materialize.

Bandits Were Very Effective Promise Enforcers

Enter the meatheads, warlords, and security agents who provided rule of law as a for-profit service to Russia’s first businesses in the 1990s. These “violent entrepreneurs” protected the life, liberty, and property of business owners better than the Russian state itself. In the process they made a killing and served as an extremely rare natural experiment in how monopolies of violence form.

The first, and most famous strain of these violent entrepreneurs were the bandity (“bandits”), another name for Russia’s mafiasos. It goes without saying that the bandits are and were terrible. Without exception. Anyone who makes a living from beating people up (or threatening to), or (even worse) sets out to make an entire organization where that is their business model, is terrible.

But they ended up providing the rule of law that many Russian businesses needed, even if it wasn’t the one they deserved. And though they occupy a very dark-grey moral area, they’re worth studying. We can learn a lot about how and why our own rule of law works by examining their outsider statecraft. What we see in both our regime and in their regime is likely intrinsic to a good rule of law itself.

Bandits were not a fringe presence in Russian business life. But sizing their market share is somewhat difficult. As you can imagine, businesses wouldn’t be eager to report that they pay for the services of a criminal enterprise. The hard data is spotty, but we do have a quantified lower bound. By 1997, 17% of small businesses and 4% (!) of large businesses still depended on bandits for protection.

This was after the worst of the transition had passed, after the arbitrazh courts' times had improved significantly, and after arbitrazh had its own enforcers. Many interviews and criminal databases show that bandits were prevalent, especially earlier in the transition (we'll discuss why below).

Bandits emerged from Russia’s martial arts gyms. The original bandits were semi-professional wrestlers LARPing Goodfellas. Like everyone else around them, the bandits were completely new to their trade. Their initial training consisted of watching mobster flicks from America and Hong Kong, imported from overseas through Russia’s newly opened trade corridors.

These martial artists, who got into the Russian rule of law industry at its ground floor, set its center of gravity. A good 3 in 5 of the founding wave of bandits were wrestlers, boxers, or disciples of kung fu, judo, or karate. These first bandits were overwhelmingly young, most aged 18-24. But this wasn’t just a spontaneous process of dudes getting black belts and then pursuing a life of crime. It was a trend that came from surprisingly high ranks of sports institutions.

Many of the leaders in Russia’s martial arts circuit were also pioneers of Russia’s extortion-protection industry. In 1994-1995 alone contract hitmen took out the vice president of the World Boxing Association, the chairman of the Russian Professional League of Kickboxing, and the founder of the International Academy of Martial Arts — all of whom had dazzling parallel careers in protection racketeering.

Initially, bandits made their money from extortion. This was an easy first business: there were many new businesses to extort in the late 1980s, and police still saw entrepreneurs with the radioactive glow of criminality because culture and mores change slower than the Supreme Soviet can pass laws. But the good times didn’t last.

Over time, there were no more new businesses to extort. So the market entered a zero sum phase, where the only way for a bandit to grow their market share was to take from someone else’s. “Customer retention” was now paramount, so the bandits shifted their focus from extortion, e.g. simply terrorizing businesses for money, to “protection” - e.g. preventing other bandits from terrorizing their businesses for money.

But as customers’ business grew, demands for protection became increasingly complex. At first it was simply a matter of physically protecting your customer from other bandits. But table stakes features of rule of law quickly got elaborate to keep up with customer needs. Here’s Denis, a lieutenant for a Petersburg bandit crew explaining his team’s services to Vadim Volkov (the sociologist whose book Violent Entrepreneurs inspired this series):

Volkov: What did you do actually?

Denis: Well, we had a large warehouse, for example, and we checked potential customers [i.e. those who loaned goods for retail trade - VV], collected information about them, went to see their offices, found ways to arrange the whole thing so that they could not cheat. On the whole, we worked as an ordinary security service. Or when those businessmen could not pay back on time we met other businessmen’s partners, so to speak. We asked them [the “partners” [[aka the counterparty’s bandits - AA]]: ‘do you vouch for him?’ And they did, or conversely, if our businessman could not repay, we worked out a payment scheduled, calculated when he could repay and gave our guarantees.

Volkov: Was it not easier to cheat?

Denis: What for, then there will be a conflict, and we’ll have to hide. Who will run the business while we live on the mattresses? They cheat when the money is really big.1

Putting the above in finance lingo: Bandits conducted due diligence on their customers’ wholesale clients for working capital financing, helped their customers restructure their debt, and provided guarantees (backed by force) to their customer’s counterparties. Volkov even cites examples of Franken-statecraft, where entrepreneurs would get a legally binding decision from arbitrazh and then hand the decision to their bandits for who would then go collect it (!). Just a few years in, and the Russian bandits were much more familiar with violent promise enforcement than the Robert DeNiro and Joe Pesci characters that first trained them.

Bandit rule of law was based on reputation for use of force. Bandits gossiped with each other. Their gossip webs formed one big lore circuit that allowed them to turn episodes of violence, particularly colorful ones, into reputations. These reputations worked very similar to the reputations in our own lives.

For example, bandit employees had their reputations in their bandit gangs, and their bosses might promote them for particularly valiant work. Here’s one criminal enforcer, Vadim, explaining how he got fast tracked for management:

Once we guarded a cargo train that had two platforms with expensive cars for [Nursultan] Nazarbaev [then-president of Kazakhstan]. Each car was worth sixty thousand US dollars. The train suddenly stopped in an open field. Some bandits pulled up and wanted to unhook the car platforms. And there were many of them. We pulled out guns and started shooting along the train to keep them off, just to win some time, because we had managed to connect by radio to a nearby military helicopter unit and to call a helicopter. When it appeared they understood it wouldn’t work out for them and retreated. After that I was given my own brigade.2

For most of us, we’d expected to put in extra hours, perhaps help estimate a few more tickets, and write product requirements for our team to get that promotion. For Vadim, he had to call in military attack helicopters to fend off an attempted heist of motorcade vehicles.

Even more important than internal reputations were external ones, between bandit gangs. The bandit gangs used these reputations to gauge the “seriousness” of their industry peers. The Literature is rich with colorful stories of how bandits settle disputes. You’ll find lore of bandits driving hijacked tanks to their rivals’ offices. Or of bandits calling in fighter jets as reinforcements to a meetup. Bandit gangs built their notoriety off of stories like this.

And ironically, these stories helped gangs, and the bandit justice system writ large, reduce the actual violence needed to resolve individual disputes. If you knew that someone wasn’t afraid to get forceful, you’d think twice before you went against their word. If you didn’t do as they said, they would have to beat you up (or worse) to preserve that reputation. Bandits preferred not to have to use force if they could avoid it, and they even had a term “frost-bitten” to describe someone who was overly eager to use force. As a measure of their cultural footprint, this term entered the public’s vocabulary and was even used by a politician to characterize a NATO airstrike campaign that he considered overly zealous.

A bandit with a reputation can issue a credible threat. That threat is also a promise, but in its bizarro bad guy form, and only guaranteed by the bandit's track record. For example, if you walked through the markets of Petersburg in the early 1990s, you’d see kiosks displaying hand painted signs that read “Security provided by A.I Malyshev”, name-dropping a prominent local crime boss. This was a credible threat: A.I Malyshev (whoever he might be) would find you and you hunt you down if you harassed one of these stores. And with it, the stores were left alone.

Bandit justice scaled upmarket remarkably well. The bandits started out protecting businesses in the shadow economy, and the layer of the formal economy that interfaced with the informal, primarily wholesalers. But due to gaping holes in Russian commercial law and enforcement, bandits offered rule of law to a surprisingly large number of large organizations. By the end of the 90s, even after the protection industry had gone legit (more on that in a bit), at least 4% of large enterprises still relied on criminal groups for protection.

That number was collected in a survey done by academics, and almost certainly underrepresents actual upmarket traction. Volkov says the bandits’ customers included Baskin Robbins (!) - so mobsters got a cut of every 31-flavored scoop. They also oversaw scores of transactions that flipped state enterprises into private hands.

For some time, bandits were much better at collections than the Russian state. Without the ability to print their own money, the bandits had to earn their revenue. Bandits were an appealing enforcement option for many Russian businesses in part because of their cost—10-15% of gross revenues, or 40-50% of collected debts. Compare this to the 80-90% aggregate tax rate across the Russian state’s national, regional, and local levels. The only way the bandits could sustain themselves at this “low” tax rate was with airtight collection departments.

The really enterprising ones conducted reconnaissance on your trading partners and knew where they stayed, where they kept their cars, what properties they held under their wives, children and siblings’ names. And they had no qualms breaking through limited liability shell games to collect what you owed. You could play dead with arbitrazh enforcers, but that was a much more dangerous game when bandits came knocking.

Many bandit organizations installed their own accountants (!) to book manage and audit (!!) the finances of the companies they protected. If you owed them money, or had otherwise entered into an agreement with them to swap one of their assets (muscle, reputation, connections) in exchange for a claim on your future cashflows, they required due diligence on your ability to repay.

Hence bandits’ emphasis on getting very good at auditing and accounting. One bandit once said to a Moscow journalist:

If [government] tax inspectors had learned to work with businessmen as we do, the state would have no problem collecting taxes. Have you ever heard, for example, of someone offering a bribe to our auditor?

If a professional wrestler can brag that he a runs a better tax collection department than you, an authoritarian government with a massive surveillance apparatus, then maybe you have some soul searching to do.

Speaking of the Government’s Response: Private Protection v2

The Russian government’s response to the bandits was weird, but clever. Normally at this point in the movie, the police commissioner announces a war on gangs and begins scouring the city for the criminal warlords terrorizing our streets. Hans Zimmer strings start playing with a zoom-out arial shot of the overcast city skyline. Of course that also happened, and the Russian government set up various anti-organized crime initiatives. But they didn’t stop there.

Remember that there was much more going on at this time in Russia than just the formation of its capitalism. As part of the transition out of the Soviet regime to a sovereign Russian republic, the intelligence and security ministries underwent intense restructuring and downsizing. The security agencies laid off, dismissed, or furloughed hundreds of thousands of agents due to dwindling budgets.

At first the security ministries started a program where underemployed agents could work in the private sector, often at banks, as “roofs”, slang in Russian for private protection agencies. In 1992, they cemented this arrangement with a law that made private protection legal called “About Private Detective and Security Activities in the Russian Federation”.

Why would Russia legalize competition for its monopoly on violence? Russian intelligence managers wanted the laid off agents to make productive use of their relationships and keep them within the sphere of influence of the Russian intelligence community.

Once Russia legalized private protection, thousands of agencies formed. What was meant to be a jobs program for laid off security officers became a turning point in the rule of law industry. The supply shock permanently transformed the pricing model for rule of law. For the first time, Russian businesses could purchase justice-as-a-service for a fixed cost (of only $100-600 per month!). After 1992, all the easy profits boiled out of the market.

In addition to better pricing, it expanded the range of personalities in the rule of law market. By 1998, the private protection industry in Russia employed over 850,000 people, with nearly 1 in 4 of them licensed to carry firearms. It wasn’t just intelligence and security officers who got in on the action. Legal private protection allowed Russia to integrate many veterans of its war in Afghanistan into the market economy. The Herat Organization, for example, a roof named after the province in Afghanistan where its founders served, employed nearly 5000 people by the end of the 90s.

This changed the culture of the industry too. Many businesses began the heroic process of cutting off their ties with bandits for less violent, less criminal protection. With these characters, the importance of access to government intelligence databases and quality reconnaissance became relatively more important. Meanwhile, a reputation for violence became relatively less important. But the informal economy still had ample need for bandits, so their strongest market position was with smaller and medium size wholesalers of fast turnover products selling to mom and pop retailers.

For many industries in the 90s, private protection became a table stakes requirement, like legal or accounting. With justice priced so democratically, it became a standard for people doing business. So standard, in fact, that many banks would check in with your roof as part of their diligence process for financing:

A Moscow company applied to a bank to finance the lucrative deal but the bank demanded that its “roof” should first meet the “roof” of the trade company. The [trade] company did not have a “Roof” and its director had to urgently find an old “friend” who dealt in private enforcement and ask him to join negotiations with the bank as his “roof.” The loan was issued under the guarantees of the “friend.”

Again, here again is the importance of a credible promise. Would a bank trust that you could (and would) repay if you didn’t have a roof that could hold your trading partners (and you, frankly, as well) accountable?

The government legalizing the protection industry meant that at least Russian businesses could get the rule of law they needed, without relying on criminal enterprises.

What This Mean for Justice?

There are a few lessons to learn from the market-driven need for rule of law in Russia’s transition decade. You’ll find this relevant if you want to better understand how business interfaces with government, OR if you want to understand why certain people, or certain groups, find themselves at the center of seismic, historic changes.

States are businesses. The traditional story of state formation involves force: forcing people to pay you taxes, forcing people to follow your rules, et cetera. People who study states and how they form fixate on the role of force, probably to a fault. They flatten the process down to a hostage situation: armed, buff dudes take a territory forcing everyone within it to pay them a tribute.

Sure. That happens sometimes. But Russia’s bandits reveal an embarrassing blindspot in that story. Russia’s state was plenty strong—it had the world’s second most powerful military, nuclear weapons, a sweeping surveillance apparatus, and was coming out of an authoritarian regime where all the infrastructure, especially the financial infrastructure, was under their control.

So how did the bandits get so big that they were able to build multinational conglomerates and form their own political parties? They served the needs of a massive market segment, and provided an actual functioning rule of law. They broke the Russian state’s monopoly: not just on the use of force, but—more importantly—on tax revenue. They reinvested their earnings to grow their operations, and acquire new customers.

History is replete with episodes of this rough narrative shape. Competent statesman realizes that they can make their jurisdiction a magnet for taxable cash flows by making themselves useful to businesses. They set up institutions that make it easy to stay compliant, help protect businesses in transactions, and do what they can to encourage businesses in their realm to grow. Many of those businesses do grow, and the state has more revenue, which it uses to build itself up and become more robust.

People who fixate on force think that these pro-business states are simply better hostage-keepers, namely that they charge less in taxes. That’s some of the story—of course businesses don’t like to pay taxes. But they also do want robust protections, and they would prefer robust protections over zero taxes. This is why you don’t see any big businesses flocking to re-domicile in Somalia, despite its highly favorable tax environment.

History is made by midwives, not great men.3 History’s alpha accrues in the transitions. The people who broker transitions are the people who make history. That makes you wonder, who gets to broker history's transitions? It’s the people who are closest to the site of transition who have the skills and values necessary to give the world what it needs to transition. This explains the paradox of Russia's bandits outmaneuvering the state.

Russia needed promise enforcement in order to transition to capitalism. The bandits, while jerks, were reliable jerks. They did what they said they’d do more consistently than any other “enforcement partner” that businesses could access, including the Russian state. In a chaotic market, they were order-making. Bandits could make your counterparties (and you!) honor promises—regardless of inflation, political climate, illiquidity, or whatever.

Their culture was well-suited to the moment. The bandits’ warrior values, combined with reputations built through gossip, allowed them to scale trust. Person-to-person relationships which were the main “trust technology” that at the time, as the Russian state had never enforced a functioning rule of law before. The bandit social network, which had no trouble spanning Russia, made it easy to enforce agreements across cities.

And of course, the bandits were adaptive and fast-moving. These virtues are important in any transition, because transitions happen fast. By the time the Russian state caught up, the bandits had become a fixture of the business landscape, and compounded their growth through reinvestment. They saw that the easy racketeering money wouldn’t last forever, so they pointed their reinvestment efforts towards buying legitimate businesses. To this day, the founders and leaders of bandit organizations are part of the fabric of Russian society. Russian political candidates for office are routinely (and credibly!) accused of having ties to 90s bandit organizations.

That’s it for the bandits: they paved their lane by having the right skills (and values) at exactly the right place and time. They gave Russian businesses a viable legal runtime by enforcing promises.

In the next part of this series, we’ll discuss how the Soviet banking system navigated this transition.

Bibliography

Arbitrazh Procedure Code, 2002. https://www.wto.org/english/thewto_e/acc_e/rus_e/wtaccrus58_leg_61.pdf

Gray & Hendley. Developing commercial law in transition economies: Examples from Hungary and Russia. In The rule of law and economic reform in Russia (pp. 139-146), 2019.

Kathryn Hendley. “Remaking an Institution: The Transition in Russia from State Arbitrazh to Arbitrazh Courts.” The American Journal of Comparative Law 46, no. 1 (1998): 93–127. https://media.law.wisc.edu/m/zdkym/ajcl_1998.pdf.

Vadim Radaev. "Russian entrepreneurship and violence in the late 1990s." Alternatives: Global, Local, Political 28, no. 4 (2003).

Vadim Volkov. Violent Entrepreneurs: The Use of Force in the Making of Russian Capitalism. Cornell University Press, 2002.

Volkov.

Volkov.

According to Google, the word “midwife” is gender-neutral. Kind of like “husbandry.”